Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

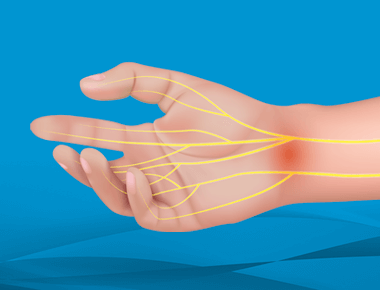

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a condition that causes numbness, pain, and tingling in the hand and arm. It occurs when the median nerve, which runs through the hand and wrist, is compressed. Dr. Christian Skjong explains how physicians diagnose and treat carpal tunnel syndrome to prevent it from progressing over time, and what to expect should you require carpal tunnel release surgery.

Hosted by Eric Chehab, MD

Episode Transcript

Episode 6 - Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Dr. Eric Chehab:Welcome to IBJI OrthoInform where we talk all things ortho to help you move better, live better. I'm your host, Dr. Eric Chehab. With OrthoInform, our goal is to provide you with an in-depth resource about common orthopedic procedures that we perform every day. Today, it's my pleasure to welcome Dr. Christian Skjong, who will be speaking about carpal tunnel surgery. As a brief introduction, Dr. Skjong graduated from Carleton College, summa cum laude, with a degree in biology in 2005. He enrolled in medical school at the university of Chicago from where he graduated in 2009. He stayed at the University of Chicago for his residency training, which he completed in 2014. Following his residency, Dr. Skjong did his advanced training in hand and upper extremity surgery at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Finally following the completion of his fellowship, Dr. Skjong joined the hand and upper extremity service at Illinois Bone and Joint in the Glenview-Wilmette division. Dr. Skjong has received numerous awards throughout his academic and professional career.

He played varsity basketball at Carleton College and was selected to the all-academic team for the Minnesota intercollegiate athletic conference. He was selected Phi Beta Kappa in 2005. He received the Basic Science Research Prize in 2006 and received the highly competitive Medical Student Research Fellowship from the Orthopedic Research and Education Foundation in 2008.

Dr. Skjong is also an accomplished musician. And if I have the story correct, was signed to a record deal during his college years and took a year during college to pursue a career. Though he never became the rock star musician, we all would like to be. He’s certainly is a rockstar orthopedic surgeon and has exceeded all expectations during his first five years with Illinois Bone & Joint.

Dr. Skjong has helped thousands of patients on the North Shore with hand and upper extremity disorders and has been praised by his patients for his kindness, compassion and clinical excellence. Christian, welcome to OrthoInform, and thank you for being here. Thank you for having me. We're here to discuss carpal tunnel surgery, and I guess the place to start is what is the carpal tunnel?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Uh, That's always a good place to start. In a lot of orthopedics, everything is based off anatomy. So, the carpal tunnel, very unimaginatively, is named after an actual tunnel, just in our wrist. If you look down at your hands, Where the forearm kind of attaches to your hand. The bottom part of the hand is technically the tunnel itself.

It's made up of a few landmarks on the backside. It's made up of the bones. There are eight little bones in your wrist. That's the backside of the tunnel. And then the top is a ligament that runs over the top of that tunnel. And then through the tunnel runs all of the tendons that lets you make a fist.

And then the main nerve that we're going to be talking about today, the median nerve.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

When patients have issues with the carpal tunnel, what generally are those issues?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So most folks will start by feeling some sort of discomfort. It's a little patient dependent, but most folks will either complain of numbness and tingling. The median nerve. The nice thing about nerves is that they give a very specific area of real estate that we can kind of map out on the body. So, the median nerve is responsible for giving us sensation. Thumb index middle fingers, and then often half of the ring finger. Folks will often notice some numbness or tingling in that distribution.

And it varies depending on the time of the day. Some folks will get it with certain activities like driving prolonged distances. Uh, if their job entails a lot of typing or gripping. Or very commonly nighttime symptoms come into play. People will wake up in the middle of the night with their hands numb and tingly, feel like they have to shake it out or hang it over to the side of the bed to wake it back up.

Often in the later stage, people will start to notice some changes in their motor function.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So what do you mean by that?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So if you do it, the nerves are splits kind of between giving us sensation and allowing us to kind of interact and feel things throughout the world. But often they're responsible for motor as well.

So they control some of the muscles, and in our hands, they're responsible for some of the little muscles in the thumb and some of the little muscles in the fingers. So folks will notice a weakness in pinch, you know, opening jars or keys. People often complained about putting on like shirts or buttons.

Uh, you get clumsy. People often think they started to get clumsier, and that's often a later finding when the nerve has been affected, for a period of time.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So what is it about the carpal tunnel? Does it change as we get older? Why suddenly do people as we get older, have these symptoms that are related to the median nerve?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

That has evolved as we've kind of studied this over the decades and, 150 years since it's been first categorized. A lot of it is related to just how we're built and the function of our hand. With that tunnel, having a limited finite amount of space, and with the tendons running through it, we use our hands, all day long for everything. So sometimes it's not that the tunnel itself changes. It's just that we overuse the soft tissues in our hand, or the tendons get swollen or inflamed. And it just creates less space for the nerve, which is unfortunately sitting very superficially in the tunnel. Uh, you can have other changes that can be related to other medical conditions. Sometimes rheumatoid arthritis is a culprit, folks with diabetes, thyroid conditions. Those medical conditions change kind of the milieu of our cellular workup and cause certain tissues to either swell or get larger and take up more space, which functionally just decreases the volume in that tunnel.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. So, let's say a patient comes to you. They're experiencing symptoms of carpal tunnel, or they're being awakened in the middle of the night by the burning in their hands. They're having difficulty buttoning their shirts. They're dropping things like you're mentioning. What are some of the things that you're looking for on your clinical exam to help you diagnose carpal tunnel because there are some conditions that mimic carpal tunnel, correct?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

There are, and that's the difficult part with the hand or the wrist in general, there are so many moving parts in so many tiny little bones and tendons and ligaments that all work beautifully in concert when they're working well.

It's kind of amazing that they work as well as they do, as long as they do, but arthritis can mimic pain, uh, like a carpal tunnel syndrome, specifically thumb arthritis. We see a lot of, we call it basil or joint arthritis. We tend to make things sound fancier than they are, but that's basically just arthritis at the base of the thumb, uh, that can cause inflammation and irritation that can mimic carpal tunnel syndrome, basic tendonitis, overuse type injuries.

You're doing a ton of typing, or if you have a more of a manual type labor job doing a lot of hammering or fine motor stuff mimics carpal tunnel as well, but it's often tricky to tease out what exactly it is. A lot of the diagnosis initially, when people come in is based off of just clinical exam.

Right? Exactly what they're feeling. You kind of take into account what they do for a living and how they are presenting from that standpoint. From a physical exam standpoint, this technically so carpal tunnel syndrome, we, you know, is orthopedic. We get a lot of x-rays. We get a lot of MRIs and, and other fancier tests to look into the diagnosis for things.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is actually one of the few things in orthopedics that you technically can diagnose based solely on clinical exam. So there are a few physical exam findings we look for just specifically when looking at the hand, and when someone presents a late stage finding, which usually people won't present with initially, but it's a dead giveaway on physical exam.

The median nerve that gets pinched and carpal tunnel syndrome kind of controls the muscles in the thumb. So at the base of the thumb, help you move your thumb around and pinch. So in a late stage finding, people will have a big divot in their muscles. So if anybody looks at their hands and they'll see kind of the muscle looks like it atrophies, gets smaller with time, you get that divot.

It's a dead ringer for bad carpal tunnel syndrome. Prior to that, the physical exam findings are based on us testing the nerve and how irritated is around the carpal tunnel. So we do certain little strange tests. One is called the Tinel's test, where we basically tap over the carpal tunnel on the person's forearm and palm.

Uh, and if the nerve is very irritated or pinched. Bothers people a lot. Uh, you'll get little kind of zingers. If anybody's heard of sciatica out there from back issues where you get little zingers shooting down the leg, the same thing happens in your arm. A little electric shocks that shoot down the fingers.

So that's the Tinel's sign. Another very common test we use is something called the Durkin's compression test. It's just where we kind of force pressure down on top of the carpal tunnel on the palm by just pressing on someone and flexing their wrist.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So you're restricting the tunnel a little bit further.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Exactly. Yep. You're basically recreating kind of carpal tunnel syndrome for the most part. And you just hold folks there for a few seconds. If the nerve gets irritated, they'll get the numb tingly feeling in the thumb, index, middle finger or a variation thereof. And that's kind of a sign that they have it as well.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Do any use for the, um, pinprick sensation and the differentiation between one and two points. It's been a long time since I've done that.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

They call it the Semmes-Weinstein testing, where it's you take these little filaments basically, and you kind of poke at the finger.

The nerves are so hypersensitive in our fingers, which is unfortunately why often things in our hands bother us so much, but we interact and experience the world through our hands. So those nerves are so perfectly tuned that they can pick up tiny little pinpricks and they can pick up little distances between tiny little pinpricks of the, in the distance of millimeters.

So when the nerves get irritated or if you have longstanding carpal tunnel, the nerve just starts to work less well. So all of those fine kind of differentiations become less distinct. We often will use those little filaments or test just like you said, two point discrimination, which basically you can think about if you unfolded a paperclip and you kind of put those two ends of the paperclip together and you poke the two pieces down onto the finger.

And if somebody can say, oh, It's one point or two points, and then you slowly just bring those points farther and farther away, so that you can discern either very close distances or far away distances. In bad carpal tunnel syndrome, it's harder to discern those fine points. So it gets to the point where it's, you know, farther and farther away–

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Two pinpricks feel like one. And no matter how far apart, you have to put them very far apart for people to distinguish, because again, the nerve just isn't working well, isn't working efficiently. Yep, exactly. And then there are also some changes in the glands in the hand, you'll see some, some drying of the hands.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Yeah. Those are kind of the strange symptoms that folks get that we often don't associate with nerve function, nerves, or, you know, wildly important for us.

They control not only the sensation and the muscle, but all of the small little capillaries or little blood vessels in our fingers. Some of the glands that our sweat glands and things, so folks will start to get dryer hands. Another common complaint is an itch, uh, in your hand or your fingers that you can't scratch.

It sounds very strange, but the fingers kind of itch and people will scratch it, but it doesn't go away. It's just because of how the sensory kind of changes the, the glandular stuff in the fingers. It's kind of amazing.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. So there's a lot, obviously that you look for in physical exam, you get a lot of information from history.

And you had mentioned that there's not really any specific tests, like an x-ray an MRI, that makes a diagnosis, that's typically made off of clinical and clinical exam and clinical history. Uh, there are some tests specifically electromyogram and with an EMG, what's the purpose of that test? And what information does that give you about your patients with carpal tunnel syndrome?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So we use EMGs, again, you're spot on where the carpal tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, but that EMG just like you said, it's often split into two pieces. One part is the EMG part, the electromyogram that tests, the muscle response, two signals traveling down the nerves.

And then the flip side of that is something called a nerve conduction study or a nerve conduction velocity study, that tests how well the signals travel down your nerve. So an EMG is one of the only tests that can give us objective data, everything else being subjective based on how people perceive their symptoms.

So the EMG can actually test of how well the nerve is functioning. So it gives us that objective data. So we will often get an EMG in folks just to help confirm the diagnosis. It actually serves multiple purposes. One is to say yes or no to carpal tunnel syndrome or other compressive neuropathies in the arm.

It can also delineate nerve pinches in the neck, cervical radiculopathy, which helps us to tease out whether something is actually carpal tunnel, or if those symptoms are coming farther upstream from the neck.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So if the nerve is compressed, farther up and not in the wrist, it can still give symptoms that would be similar to a couple of tunnel and then doing treatment for carpal tunnel when it's a problem in the neck would be pretty ineffective, obviously.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Correct. So that's the tricky part with those nerves. Anything downstream can be affected in a very similar way. So that nerve study kind of helps to tease that out. It says yes or no to a problem, but then more importantly, what the nerve study does is that it often will chop it up into different subcategories. So mild carpal tunnel syndrome, for example, moderate, severe, and then very severe. And then those sub categories are what really kind of drives our treatments for how we chase after carpal tunnel syndrome.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then like an X-ray, an EMG does have some variability based on who does it, right?

It's not a test that is easily reproducible, so there's some variability in the test. I don't know if there's variability from one time you take the test to the next or from one person doing the electromyogram and performing the tests.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Probably a little bit of both. That's always the tricky thing with a test that tries to be objective.

There are probably a few percentage points that swing both ways, positive or negative. And there is some interpatient differences, there is or intrapatient, in the same person, if they got it multiple times, there is some variation in terms of who is doing the test as well.

We work with some really good folks who do a fantastic, super thorough job and have been able to reproducibly do it for decades, which is great. So we're fortunate to be and work where we are, but that is very true. There is some variability in that testing.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Let's take a patient who presents to you with some of these signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome.

And I'd like to just discuss briefly some of the non-operative interventions for carpal tunnel.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Once we kind of diagnose carpal tunnel in someone, both between the clinical exam and that EMG test, the treatments kind of start to open up, based on how they feel and how progressive their symptoms are. We always try to start non-operatively, if we can– that's not always possible with carpal tunnel.

Some folks will present a little bit later, but, for the non-operative approaches, it basically falls into three main categories. Uh, one is activity modification. So if we can kind of drill down into what the person does on a daily basis and figure out that this person's symptoms always happen when they drive to work, or it always happens when they're at work typing for prolonged periods of time.

If you can pinpoint a certain activity that seems to be aggravating the carpal tunnel syndrome, then you can work to kind of modify that. Driving is a little bit difficult, but you can try to either adjust the size of the steering wheel and strange as that sounds, you can get little kind of over wraps.

It's the same thing as overwrapping a tennis racket or a golf club, just making the grip a little bit wider that tends to take pressure off of the carpal tunnel. That falls into play for a lot of truck drivers or long haulers who have to get out there and kind of drive for a long period of time. For desk type folks, a lot of it ends up being the classic kind of ergonomic assessment. Right? Make sure your desk is the right height, make sure your arms and your wrists. Aren't kind of flexed or extended at work. Have a pad that you rest your palms on. All of those things can be the activity modification kind of angle.

And then we kind of up the ante from there. Uh, one of the mainstays of treatment for non-operative treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome is bracing the wrist. And it's usually bracing at night. The way we're built.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Why at night? Is that because that's when the symptoms tend to be most aggravating?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Yeah. One of the main common presentations again, is that nighttime symptom where we'll wake up in the middle of the night. And the hand's, very numb and tingly, and you have to kind of wake it back up. And the reason for that is usually twofold. One is at night we tend to curl up. That's just how we're built. The flexors in our arm and our hand are strong.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And so that position of curling up is compressing the nerve?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Yep. It's that fetal position that just mechanically creates less space in that tunnel. It just makes it get pinched and causes trouble. So the bracing at night just holds you in a neutral position. Doesn't let you flex your wrist. Hopefully it takes pressure off the nerve and makes those symptoms a little less aggravated. The other tricky part about nighttime is that you're not moving a lot. So during the day, we're constantly doing something and we're shifting positions. So even if the nerve gets pinched for a few seconds during the day, a few seconds later, you've moved and it's taken pressure off and kind of changing things. So at night, it's the combo of being flexed and just staying like that for a long period.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And so between activity modification, splinting, and then–

Dr. Christian Skjong:

The third angle is a steroid injection. We use steroids, obviously an orthopedics, for a lot of different things. Tendonitis, arthritis is the big hitter.

You get injections for arthritic changes in the knees, shoulders, everywhere. Uh, it's done a little bit differently in the carpal tunnel syndrome, but we do do steroid injections as another kind of third angle approach for non-operative management. And the purpose of that is to try to use the anti-inflammatory effects of the steroid to try to decrease any inflammation in the carpal tunnel, or just calm down the nerve. It effectively tries to either calm down the nerve or create more space and volume in the tunnel itself.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Earlier, you mentioned that there are some patients who really can't be treated non-operatively– describe that patient. And then we'll talk about more of the operative treatment as well.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So those folks who come in with that muscle atrophy that I had mentioned before, that's the very, very classic sign of a very longstanding late stage, severe carpal tunnel syndrome. Uh, the muscle atrophy, it means that the nerve has been very irritated for a long period of time. Once you get to that point, it's very unlikely that the non-operative measures will significantly alter the natural course.

So in those folks, if they come in with a Thenar atrophy, it kind of pushes us towards intervention, the reason being is that the nerves are a little bit trickier. If you think about arthritis, the natural history of arthritis, say in a knee, is that once you get it, it tends to continue to worsen. I tend to use a lot of silly analogies in clinic, but it's akin to driving your car.

You have tires, brand new tires on your car. Beautiful tread. The mechanics are always yelling at me about the tread on my cars, but the longer you drive the car, the more you wear out your tires. So arthritis is the same way. We bang up our knees and walk and do things for decades and decades. And you wear away the cartilage and you get arthritis.

That tends to get a little bit worse, but no matter how far you are on the progression of arthritis, if you ultimately needed a surgery for like a total knee replacement, a very successful new set of tires. The hard part with the nerve is that if you progress from that mild to moderate, to severe, to permanent changes, once you're in that camp, even the surgery for it, doesn't allow it to recover.

So you can get in, unfortunately into that permanent change, where if you wait too long or we don't get to it soon enough, then you, even with us intervening in the most aggressive way we can, you're still left with significant deficits. So those folks, it's unfortunate, but you often have to get to that surgical side of things sooner than later.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then the other folks, the more common patient who doesn't have that severe stage of carpal tunnel syndrome, but who's perhaps done the injections, the splinting, activity modification, but still suffers from the symptoms. How do you indicate that patient for a procedure?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So often it's based on their, responsiveness to prior treatments.

We often, if you're in that mild or moderate category, even on the nerve study, or if they've only had it for a short period of time, we often will start with the bracing activity, modifications and injection, and then see how they respond. The data is a little bit all over the map for carpal tunnel, because it's so subjective of a thing.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Sure–

Dr. Christian Skjong:

But the data shows that if you are in that mild or moderate category, and you let's say get a steroid injection, about 80% of folks will have really good relief. But only about 20% of those folks will have persistent relief after a year. So it tends to want to come back. So if we did, let's say a patient, came in. We tried bracing, gave him a shot. They felt great for six months, six months later, they gave me a call and they say, hey, it's coming right back. Just as bad as it was before. That's when we start to look into considering doing the operation. Between the recurrence of the symptom and the failure of that conservative management and the downside of a waiting, uh, and with the potential of permanent changes that tends to push us towards the surgery for it.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So any preparations that a patient who's been indicated for carpal tunnel needs to make, there's not much really to do ahead of time. Is there?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Not really. Unfortunately, it's similar to anyone who has arthritis or tendonitis motion. It helps us just keep things kind of loose. It's human nature to, you know, if something is uncomfortable or hurts, we tend to modify our activity, or kind of tuck it in at our side and kind of hold it off to the side and not use it, which tends to make it feel a little bit better in the short term, because you're not poking at it, but in the long-term, again, all of those moving parts in your hands get stiffer and weaker and stiffer and weaker.

So you kind of are setting yourself up for a little bit of a worse result for that.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. And then on the day of surgery, this is a procedure that can be done under many different types of anesthetics. So just take us through the surgical day for a patient. What can they expect on that day of surgery?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Yeah. So if you, a weird way, if you have to have surgery a carpal tunnel release is like the type that you would want to have. On a spectrum of severity, a carpal tunnel release is very much on the nice side of things. You can do it very much as an outpatient– the vast, vast majority of these are done as an outpatient, so done at a surgery center. You can technically do it under straight local anesthesia, meaning that you don't have to have any sedation. Uh, we basically numb up the hand, and do the surgery that way, very comfortable for folks. You don't really feel any pain. And then you kind of go on about your day. Uh, the surgery itself is, is quite short.

It takes, depending on the person, 10 minutes plus, or minus 10, 15 minutes. It's not very long. Uh, so the whole day, let's say you were to do it at a surgery center, you show up 20 30, 40 minutes of kind of hanging out a little bit with us. And then within an hour, hour and a half, you're home, and back to activity, which is kind of nice.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Do you splint your patients after?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So I do not. There's a wild variation of a theme on there. The data shows that you don't have to, again, this is kind of a nice one. There are a couple of things that the data within the last decade or more has borne out, which has been nice for patients.

One is that you don't need antibiotics for a carpal tunnel release. Uh, we are obviously all of us in the medical field, or outside of orthopedics and beyond have become very aware of what antibiotics are doing to bacteria and for us. So in an effort to try to curb these super bugs, that might be resistant to certain antibiotics, we're trying to target certain surgeries that don't require antibiotics. So the vast majority of people don't require any antibiotics. Uh, the vast majority of people don't require splinting afterwards. In fact, it's quite nice that the surgery usually is a little incision on the palm. You might have a stitch or two, but we just wrap the hand up in a little sterile dressing, basically a little gauze, maybe a little ACE wrap.

I usually have folks wear that for a day or two, just to keep it clean and get a jumpstart on the healing. But then after that you can take it all off. You can shower and soap and shampoo just like normal. And then if you're out and about running errands, you put a bandaid on it and just protect it that way.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then in terms of the technique of the surgery, there's the open release where you make an incision and come down to the ligament to open up the tunnel. And then there's the endoscopic procedure where you get under the ligament and then release it above. Is that, I mean, is there a preferred technique, is one proven better than the other? Is it more preference?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Yeah, it's basically more personal preference for that. The long-term data, six months or beyond, uh, shows that there's no difference between the two, you're spot on where the purpose of the carpal tunnel, it's nothing fancy. It's basically opening up the roof of the tunnel, that ligament that runs across.

So either way, just like you had mentioned the open procedure, which is through a centimeter, two little incision in the palm, or the endoscopic version, which is a smaller little incision, just in a slightly different spot. The purpose of that is just to open the roof of the tunnel. So both of those are very, very effective and the long-term data shows that they're equal.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then in terms of the procedure itself, is it typically a very painful procedure?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

No, not at all, actually. It's kind of nice. That's another thing that has, uh, that has changed in terms of, uh, post-op pain management and what to expect. A lot of folks get by with just Tylenol or Advil, which is great.

Some folks may require a day or two of stronger pain medication. But a lot of folks, if they do take the stronger pain medication, they'll take it at night before they go to sleep, just to get an extended period of, you know, some pain relief, but most the vast majority of folks, uh, throughout the day use Tylenol or Advil, ibuprofen, and then a day or two after the surgery, they're feeling pretty good where they can start to taper off from their pain meds.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And so let's go a couple of months down the road, what type of relief, what type of symptoms will patients have following a carpal tunnel or what, what types of the one they have after a carpal tunnel release?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

So the main goal again, is to take pressure off of that nerve. So the presenting symptoms of that numbness and tingling, the burning sensation that itch kind of that folks will feel often will go away relatively quickly. Some folks get lucky. Within the first day or two, they'll notice a pretty significant change, where they'll wake up in the morning and they'll say, hey man, you know what? I didn't, I didn't wake up 10 times last night, so they'll get good relief. A lot of folks with that happens within the first couple of weeks, the longer term recovery from muscle strength, or if there's further, more severe damage of the nerve tends to take months.

But that all kind of happens in the background, there's no therapy that you need to do for it. There's nothing special you really have to do for it afterwards. It's basically the, the hope is that the surgery halts the progression from making it get worse. And then it hopefully lets that pendulum kind of continue to swing back.

So the restrictions early on are few, it's basically just protecting the palm. We don't want people to put a ton of pressure on it. So we tell folks, usually for the first week or two, to try to limit their heavy lifting, pushing, or pulling, but you can still type and drive and use phones and laptops and anything that you kind of need to do.

And then after the first week or two, once that incision heals, we kind of start to cut people loose when you can get back to anything that you want now.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

It's great. I mean, people having these pretty debilitating symptoms that can be managed surgically with a very simple procedure with a reasonably predictable outcome.

But with that in mind, there's no such thing as any procedure that we do that doesn't come with some risk and complications. So what are the risks and potential complications of carpal tunnel release?

Dr. Christian Skjong:

The main risk is damaging the nerve, that is always a risk anytime we do incision on someone for surgery. There's always a risk of damaging the soft tissues or the nerve, a risk of infection.

Those are basically the two main risks, similar to any surgery that we end up doing. They're actually very low, in the surgery, especially if you as a patient, kind of do your homework and find an appropriate person to go to. The weird way medicine has kind of adapted is that it we've carved out smaller and smaller niches.

So like you’re a sports physician who does a lot of knees and shoulders. The hand and upper extremity for me. So we do, we kind of carve out our little world. So we do that. You want to go to someone who does a lot of these, just because in that setting, the risk of injury or downside is very low. It's well, well, under 1% of folks. The trickier part with a carpal tunnel is making sure that you get it checked out early enough so that you're not into that severe or permanent change. That way we can hopefully harness, you know, the benefits of a pretty minimally invasive surgery, low risk surgery, and get people back to action.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So this has been incredibly helpful for the overview of carpal tunnel syndrome. Are there any other insights that you would like to share regarding carpal tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel treatments and what resources patients have at their disposal.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

I think the biggest thing is with carpal tunnel syndrome, just to remember, and to not minimize this again, it's one of those things.

It's human nature. I'm guilty of this, where, you know, rub dirt on it. It'll get better in a few weeks and few months go by or a few years go by. And then you say, oh, geez, it's still bothering me. For the nerve related injuries, if you're having any numbness and tingling, if something just feels off or you're feel like you're not, you know, you're losing strength or your not buttoning your shirt well, call someone. Get it checked out. Even if it ends up being mild or something totally different. In this case, it's worth getting checked out just because the downsides of downplaying it or missing it can be quite significant for folks.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay, well, listen, thank you very much for joining us in OrthoInform.

Again, this is incredibly helpful and we've taken a deeper dive here in the carpal tunnel, and I think it will be great for patients to hear your perspective on the condition and what can be done for it. Christian, thank you so much for taking the time to help us learn more and understand more about a couple of tunnel syndrome.

Dr. Christian Skjong, he's our guest here on OrthoInform. Again, if you'd like more information, please visit IBJI dot com. Christian, thank you very much for your time.

Dr. Christian Skjong:

Thank you for having me.

Don't Miss an Episode

Subscribe to our monthly patient newsletter to get notification of new podcast episodes.