Shoulder Replacement

Reverse shoulder replacement has been a revolution in shoulder surgery for patients who have no function above the level of their shoulder. Dr. Craig Cummins explains the differences between anatomic shoulder replacement, partial shoulder replacement and reverse shoulder replacement. He also discusses arthritis, rotator cuff tears, pain management and physical therapy.

Hosted by Eric Chehab, MD

Episode Transcript

Episode 9 - Shoulder Replacement

Dr. Eric Chehab: Welcome to IBJI OrthoInform where we talk all things ortho to help you move better, live better. I'm your host, Dr. Eric Chehab. With OrthoInform, our goal is to provide you with an in-depth resource about common orthopedic procedures that we perform every day.

Today, it's my pleasure to welcome Dr. Craig Cummins, who will be speaking about total shoulder replacements. As a brief introduction, Dr. Cummins graduated from the University of Florida in Gainesville with a degree in zoology in 1991.

He remained in Gainesville, where he earned his medical degree in 1995. From Florida, he came to Chicago to begin his residency in orthopedic surgery at Northwestern University. Dr. Cummins completed a surgical residency at Northwestern in 2000, and then spent a year in Sydney, Australia, at the University of South Wales, where he completed his fellowship with a world-renowned shoulder surgery and sports medicine service.

Dr. Cummins returned to the Chicagoland area in 2001, where he joined Lake Cook Orthopedics (now a division of IBJI), where he's remained ever since. Dr. Cummins has been involved in a wide variety of clinical research projects, focused primarily on patient outcomes.

He has earned a certificate of added qualification in sports medicine, which only 5% of surgeons do. He has served as an instructor for the Arthroscopy Association of North America, which means he's a surgeon teaching other surgeons the most advanced surgical techniques. He is an outstanding surgeon, who has helped athletes and non-athletes alike minimize their pain and optimize their performance and function.

He is an outstanding surgeon and even a better colleague. Craig, thanks for being here.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Good morning.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So let's get right to it. Shoulder replacements, before these came about, how was the painful arthritic shoulder treated?

Dr. Craig Cummins: Well, if you just think back, over time you go back 50 years.

I think that, when people had a painful arthritic shoulder, they just cut back on their activities and took some aspirin. I don't think there was a lot they could do for it. As treatments evolved, I mean, you could do cortisone shots, but the number of shoulder replacements has gone up exponentially really over the last 30 years.

People are staying more active and they're finding that with these replacements, they can continue to be active and do things they enjoy, well into their seventies and eighties. Shoulder replacements have evolved over time. Initially it was people were doing more partial shoulder replacements where they just replaced half of the joint, the humeral side.

And those did well, it was a big advancement, but they would still get some pain from the other side of the joint, the glenoid. And there were some total shoulders being done. But the socket side was failing. It wasn't lasting that long. And then you didn't have a lot of options, you know, if you had to go around for a second operation, they weren't that good.

And then just over time, the technologies, the anatomic shoulder replacements, where you replace both sides of the joints, the results started getting better. They started seeing more and more of them done, but a large portion of the people that had problems with their shoulders from arthritis had other issues, too, such as rotator cuff tears and the standard replacements didn't do very well. If somebody had a rotator cuff tear, they tended to fail early. So, when I started in practice, which was 2001, if somebody had a big rotator cuff tear, we'd put in these partial shoulder replacements.

And to be honest, they didn't do very well. I mean, patients never got back the function they wanted and their pain maybe got a little bit better, but not that much, for a relatively big operation. And then a new type of replacement came out of, mostly out of Europe. It had been done in the past, but didn't do so hot.

And then they kind of changed the mechanics and the implant’s design, and it was called a reverse shoulder replacement. They'd been doing it for a while in Europe and the results actually were pretty good. And then in 2003, that implant got approved in the U.S. by the FDA. I was in practice early in my career when it first came about.

And I think early on, nobody really knew how well it was going to do so you would really just put them in the worst-case scenarios. You had the revision replacements where you're going back for a second go-around to operate on somebody again. But you'd put them in people with big rotator cuff tears, too, which they used to do terrible. And early on, it seemed like the complication rate was higher, but I think it was because we were putting them in these really difficult cases. But then people started noticing when you put them in these more straightforward cases, somebody that has not had surgery before, they got a big rotator cuff tear and arthritis, they did extremely well, and they recovered much faster than the standard replacement.

So what you've really seen since 2003 is the number of reverse replacements has really gone up quite a bit. Early on it was a small percent of the shoulder replacements. And I think now it's like 60, 65% of the shoulder placements done across America are reverse shoulder replacements, probably with another 40% being the anatomic shoulder replacements are 30, 35%. And then just a little bit are the partial shoulder replacements. Now the hemiarthroplasty is.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So when you talk about that evolution of really having no options other than modifying our activity to now the modern prosthesis that we can put in and the reverse being the latest iteration of a modern prosthesis, it's almost like it's revolutionized the treatment of shoulder arthritis.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And when you have a patient with shoulder arthritis, how do they present to you? What are they complaining of when they come to your office?

Dr. Craig Cummins: There's kind of a whole spectrum of how, how people present and how people feel pain and what they're willing to accept in their lives.

But I would say that the common things you see are increasing pain in the shoulder. Sometimes they had low grade pain and maybe they did something all of a sudden, it really flared up where they need to see a doctor and most of them have deteriorated function where they're not able to do as much, raise the arm up as high as they used to.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And then the thing that always puzzles me is the pain at night.

It's amazing how common that is. And that seems to be the tipping point to bringing in whether it's a rotator cuff problem or arthritic condition, and then besides arthritis or other conditions that people can benefit from a shoulder replacement.

Can you go through some of those?

Dr. Craig Cummins: The common reasons you do shoulder replacements are osteoarthritis. And traditionally that was the main reason you would do it for. More commonly, now you're doing it for a large rotator cuff tears, particularly as people get older.

One thing we've learned is that if you're repairing large rotator cuff tears and people in their seventies, they don't really heal that well, they don't do that well. Generally, if it's not like an acute tear and a 70 year old, they just have this gradually increasing pain. And it turns out that they have a pretty big rotator cuff tear, 20 years ago I would have tried to repair it.

But nowadays you tend to do a reverse shoulder replacement because it's a more reproducible operation. There's a higher likelihood of success and they recover much quicker. We're doing them for fractures. For all types of arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. The other reasons would be less common.

I suppose, if somebody had a type of shoulder instability that they're, and they're a bit older, maybe in their forties that you couldn't handle, you might consider it in those situations.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So the common reasons would be osteoarthritis, a wear-and-tear arthritis, large rotator cuff tears that are basically irreparable in older folks.

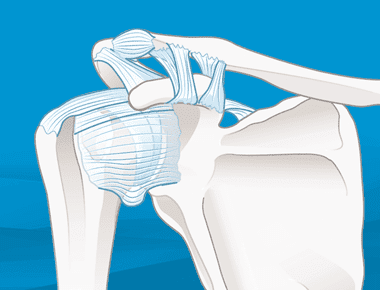

Particularly fracture surgery, where I'm trying to piece the thing back together, doesn't make as much sense as putting in a replacement. And some of the other less common problems, such as rheumatoid arthritis or instability, where the shoulder just can't stay in the socket any longer. And just for the benefit of our listeners, we've talked about the partial replacement, the anatomic replacement. So the partial replacements, where we just do the replacement on the ball side, the anatomic replacement being where both the ball side and the socket side are resurfaced.

And then you mentioned the reverse [shoulder replacement]. We didn't discuss what the reverse is. The name connotes something. So can you explain to the listener what a reverse shoulder replacement is?

Dr. Craig Cummins: Yeah, absolutely. And I think that confuses a lot of people and I really think it was a bad marketing and terminology in the beginning and they just it's too late to correct it.

Because people are like, ‘What, you're putting my shoulder in backwards first?’ and it's really–the ball and socket are changed in their location. So it is reverse, but the shoulder looks the same for the most part. And maybe a slight change in shape, but pretty much looks the same, functions like it would, if we did the anatomic, the results were pretty comparable.

It creates more of a fixed joint to some degree than you get with the standard one and which is important if you have a rotator cuff tear. It changes the tension on the other muscles in the shoulder to allow you to raise your arm up. So often when you're doing big rotator cuff tears, as you know, I mean the patients, they can't lift their arm up to any significant degree away from their body. And this changes the mechanics where they'll come back two, three months later and they're able to raise their arm overhead. And so, you wouldn't get that with the other type of replacements.

So you have to reverse the mechanics a little bit to achieve that.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And there's no question that the reverse has been a revolution in shoulder surgery for patients who literally have no function above the level of their shoulder, if that, to all of a sudden being able to use your hand up overhead. And I remember very early on in orthopedic training, someone described the shoulder purpose as being there to be able to put your hand where you need it.

Right. And right when you explain that to patients, it's very helpful for them that they realize that they have not been able to bring their hand up overhead, where they need it. And they've adapted by moving their life down. Exactly. And then when they can get their life back up again, it's a whole new world that's reopened to them.

Absolutely. And so it's a tremendous operation. It's not done as commonly as knee and hip replacements, even though it's increased in the number. Why do you think that is?

Dr. Craig Cummins: I think it's because you're not walking on it. It just doesn't, it doesn't put as much stress on it.

And one thing I've never really understood why sometimes people with arthritis, they'll tolerate it fine for years. And then all of a sudden, something happens and it becomes extremely painful. And a lot of times in shoulders, it's later in life. So I don't know the exact numbers of when the average hip or knee replacement is done, but their generally early sixties, mid-sixties. And I think the average for a shoulder replacement, you're probably in the early seventies. And not that I do this often, but I've done these replacements and the reverse replacements, more particularly, in people well into their eighties.

Dr. Eric Chehab: Meeting a patient who has a problem that would be well-treated with a shoulder replacement, what are some of the diagnostic procedures or diagnostic studies that you would perform to get them prepared for a surgery or to just in general figure out exactly what's going on with their shoulder and what would be the best treatment.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Generally, I'll see a lot of people that have already failed non-operative treatment somewhere else. And then they'll come to see me for the replacement. But a lot of patients I've been treating for years for arthritis. And there's a gamut of non-operative things you can try.

And usually, unless it's a fracture, there's no urgency to doing this. So you can kind of when it gets bad enough and on your timetable, the patients can do the replacement. But to get ready for it, I mean, you're going to, with any surgery you do is sort of standard medical things to make sure they're healthy.

They'll see the primary care doctor, probably run some blood tests for the shoulder. I mean, you need some good x-rays, and then one thing that I suppose has really changed over the last five, 10 years is the software we use to prepare for surgery is fantastic. And so we get a CT scan of pretty much everyone outside of a very straightforward replacement and it gives you all sorts of dimensions and measurements and you can anticipate any potential problem you'd run into from the bone morphology or just the anatomy of the shoulder.

And then trial different implants and put them in slightly different positions or different sizes and really customize.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And this was all before the surgery. This is a computer-generated model, right?

Dr. Craig Cummins: Absolutely. I mean, so when I walk into surgery I'll, you know, and I have it on my computer and usually the representative from whatever implant company I used print it out. It'll be like a 10-page sheet of pictures and it's really amazing.

Dr. Eric Chehab: Yeah. And then you mentioned the gamut of non-operative treatments for shoulder arthritis. Let's go through some of those for the listener.

Dr. Craig Cummins: In general, it's good to stay flexible and in shape. So an exercise program working with physical therapy, it's not going to fix the arthritis, but it can maybe prolong how long you can go before you need a replacement and you can keep your life more functional. So I think that's important. And then you start getting into medications and I think generally what you see in people with arthritis is it starts hurting more and more.

So maybe they take two over-the-counter ibuprofen before they play golf. And then next thing you know, they're taken two after golf as well. And then they see you and at some point, you might put them on a medication they take on a daily basis and that tends to, it tends to work better. But on the other hand, a lot of times these people are in their sixties or seventies and are on five, 10 other medicines and even these anti-inflammatory NSAIDs, they're over-the-counter, a lot of them and they can be safe, but they can have problems, too. So I'm, I usually I'll start someone on an NSAID. And every orthopedic surgeon probably does this different, but after a month or so, I usually will have their primary care doctor pick it up just so they can follow it.

Because you need to follow it with periodic blood tests. That works fairly well. If you sort of have a, maybe a lower level of pain. And I think people can function like that for a while. Sometimes what will happen is then, then the patient will do something, yard work or what have it.

And all of a sudden it hurts a lot more and it doesn't settle down. And I think in that scenario, we'll often, I'll often do a cortisone injection, which is a type of steroid. It's a very strong anti-inflammatory medicine. You're putting it right where the problem is, and that's very good for calming down that more acute pain level.

It really doesn't get rid of their baseline level of pain completely. And if it does, it's short term, you know, the benefit can last anywhere from a few weeks to, you know, so I have some people come back couple of years later, but I'd say on average, a few months later, people usually back to where they were. There's different types of injections. There's these gel type of injections we've been doing for a long time in the knees, viscosupplementation. There's a whole host of companies that make them and I've had some very good luck with that in the shoulder. So usually we'll try that first. For some reason, companies, they used to not approve it for the shoulder, but that's kind of gone away.

I haven't really had an issue with getting that approved. It may mean the patients have to come back a month later or something. Once we get the paperwork and everything done. A lot of people have questions about this sort of new, more biologic type of treatments for arthritis stem cells and PRP in the way.

Yeah, exactly. Yeah. I don't know what your experience is with it, but I find that for stem cells it’s more like a catch term now out there. Right? I mean, it's a marketing thing. Insurance companies don't pay for it to be $3000, $5,000 for an injection. And there's really not a lot of data showing it works.

And they're really not stem cells. At this point, it's not been proven to help. So I usually discourage people from doing stem cells but it's really, I don't think in their best interest, it's expensive and it's not proven. And I think it may work itself out over time where they, we kind of learn to use it better. So I'm glad it's being investigated. Right.

Dr. Eric Chehab: I look at it as the first iteration of hopefully other iterations that will be better than this one, because there's some, but not a lot of data that supports its use routinely for any arthritic condition, whether it's a shoulder, knee or hip. And it seems to be incentivized very heavily on the provider side because it's expensive because it's cash-pay.

And so I, likewise, I don't encourage patients to get it. I tell them if they have the means. Seeking all kinds of other alternatives that it's not an unreasonable alternative, but it's not something that I'm been willing to provide for patients simply because I personally don't see the data as compelling as it should be for the same reasons it's expensive and just not proven.

Yeah, absolutely. Similar to that is this platelet rich plasma, which is you draw blood off from the patient and then there's different ways to prepare it, but you can typically put it in a centrifuge and that separates out the various components of the blood in the centrifuge.

It's a fast spinner. Right. And the PRP, which stands for platelet rich plasma layers out.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Yeah, exactly. So you can draw that off and it's got a lot of anti-inflammatory and growth factors and other things in it that can help in certain situations in orthopedics and it's pretty straightforward to do in the office.

The results have been a bit more encouraging than they have been for the stem cells. I think it's the same concept and it's your own tissue. And you're trying to promote more of a healing environment than the steroids, which are more of an anti-inflammatory process. And I've used those in my practice.

It's generally, I think where I've had the most successes for a partial rotator cuff tear or tennis elbow where it's a tendon problem. And it's a tendon problem where it's a failure to heal, essentially and you're promoting a healing environment and you're doing other things. You're usually needling the tendon, but for arthritis there is some data, more so in the knee than the shoulder that it can be helpful for osteoarthritis and for the pain.

And so I have had success with it, but not long-term success. So maybe it'll push out the problem a year or two years. But I have not had anybody that's had more long-term success from platelet rich plasma, but it's something I'll offer to people and we'll have that discussion.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So just to summarize this idea of non-operative interventions, things we can try for patients with shoulder arthritis. Low-dose nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatories over the counter.

That's a common place where people start when they start developing pain from their condition in their shoulder, whether it's the rotator cuff for arthritis they can move on to some injections if they have a recent flare-up or an event or just the pain has been progressing despite the anti-inflammatories. We can use the gel injections in the shoulder, which had been more commonly used in the knee, but have had good success in the shoulder as well.

And then some of the other biologic, more cutting-edge, but still yet to be proven, to be very effective stem cell injections, which again is in quotes with stem cells. And then the platelet rich plasma or PRP injections, which you just described as being again, helpful for pain. The holy grail would be to regrow the cartilage and reconstitute the shoulder back to normal.

But we do not have that technology, despite all the billboards about cartilage resurfacing and restoration and everything else. We're still in the infant steps of that. And I think that's a reasonable summary of the non-operative [treatments].

Dr. Craig Cummins: Absolutely. And I think that it's going to be a long way before we're going to be able to reconstitute biological joint.

Because arthritis is more than just loss of cartilage, right? If someone falls and they knock off a piece of cartilage, you can grow cartilage and you can fill that pothole in their knee and it can do fine. But with arthritis, the bone becomes much harder.

The cartilage flakes off. The shape of the bone changes. You get the big spurs or osteophytes around the joint. So it's just a whole different environment. It's too late, I think, to reverse that.

Dr. Eric Chehab: It's a mechanically harsh environment.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Exactly.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And then, so let's get right to the surgery. If you indicate a patient for a procedure and we won't specify whether it's the partial or hemiarthroplasty or the anatomic, which is the ball and socket, where they belong, or the misnamed reverse, which is where the mechanics of the shoulder are made, so it's more of a fixed joint as opposed to a gliding joint, but let's just take, let's say someone's coming in for a shoulder replacement.

What should they expect that day of surgery? What happens are they going to come in and have it as a day procedure. Are they going to be going home and they're going to be staying at night? What can they expect that day of surgery? And then looking beyond that, what's the first week of recovery like, what's the first six weeks, what's the first six months?

Dr. Craig Cummins: Well interestingly, this has, it was evolving anyway, but COVID kind of pushed things forward a little bit in that nobody wanted to spend the night in the hospital. Right. So a year and a half ago, I would say, if I did 10 shoulder replacements, maybe one went home and eight spent one night in the hospital and maybe one of them spent two nights in the hospital.

Right. And that has really changed. I mean, I bet you seven, eight out of 10 of my patients go home the day of surgery now. So it was an outpatient surgery and sometimes the older patients will just keep them overnight just to monitor them or if they don't have help at home. Sure. So those are, those are factors.

Some things that though have allowed that to happen are the anesthesiologists I think have gotten much better than it used to be at doing nerve blocks or they numb up the shoulder and a standard nerve block will often last close to 24 hours now, depending on how they vary the concoction and then there's ways to make it last longer, which is, for some reason covered at a surgical center, but not at a hospital. But usually the anesthesiologist will do this for me. It's a Exparel and what it does is it just makes the nerve block last longer. It doesn't seem to be as dense of a block the way they do it.

But it'll last for two or three days. And usually they have function in their hand, which is good, but they don't have the pain. And it's interesting. If you can get through the first 24 hours or 48 hours, the pain is never that bad, right? I mean, my patients, they often don't take more than a handful of pain medicine after surgery.

Yep. Now there's a spectrum, so I don't want to paint too nice of a picture. You know, some people have a lot of pain. I have some people though that take no pain medicine. So I really think that nerve blocks have been very helpful. And I think the other thing is, and you kind of learned this from each other, but really I think the lower extremity joint surgeons kind of push this sort of multimodal pain management concept.

So we used to use a medicine like a Tylenol 3 or Vicodin or Norco, and it was a combination of a narcotic and Tylenol. And you know, you always worry about the narcotics, but it's really the Tylenol that you worry about because, particularly if someone's a drinker, they can go into liver failure.

So usually what I do now is I put someone on some sort of anti-inflammatory medicine. It could be ibuprofen, or if they have stomach issues, something more mild, or like Celebrex for the first three days around the clock, they take it, and then I have them take Tylenol or acetaminophen around the clock for three days.

And if you do that and you do the nerve block, you know, when the nerve block wears off, instead of their pain being a seven out of 10, it's like a three out of 10. Right. And so it doesn't get rid of all of it. And then I give them some oxycodone, which doesn't have any Tylenol in it to take as needed. And a lot of times they'll take it at night.

But really you think the first week it's really just, it's a surgery you're just recovering. I mean, I think people that work from home can make it probably be doing desk work three days later, you know, sleep sometimes it's an issue. I think if you're not getting a good night's sleep, you don't want to go back to work.

But usually I'll see them in the office, within like a week or two. And typically they look pretty good at that point, to be honest.

Dr. Eric Chehab: We've moved a lot towards outpatient shoulder replacements. The majority of them are being done as an outpatient now and COVID accelerated that trend that was happening regardless.

The pain management has gotten basically 10 times better between blocks and better choice of medications. So that patients, I think a lot of patients fear any surgery, because they fear the pain post-operatively and I think the more educated we can help our patients become regarding what we're capable of doing to manage the pain, the less likely they'll view that as an obstacle for a treatment that can, again, revolutionized their lives, they can really change their lives. And then, like you mentioned, you'll go home.

Most of the time, you'll be able to be pretty independent back to work in a couple of days particularly if you're doing a desk job, but there are some restrictions with the shoulder replacement that we don't put on, for instance, with hip or knee replacement, simply because of the way the procedure is done through a muscle approach where one of the muscles needs to be healed before you're going to have normal function of it.

And so I'll sometimes say to patients with hip replacements, you basically just walk it off with some precautions, but you're essentially walking it off. So it's a relatively straightforward and easy recovery. Shoulder replacement is also a relatively easy recovery, but it's delayed because in most instances you need to protect the repair, is that correct?

Dr. Craig Cummins: Absolutely. And probably more so than the anatomic. So yeah, when we do these replacements, we do have to detach a tendon in the front of the shoulder to get, it acts as the front door sorted to the shoulder, and then you repair it when you're done. And that has to heal, which probably takes two or three months for it to heal down to the bone.

So you want to protect that, but the one thing I would have slang or with, so usually, and this'll vary from surgeon to surgeon, I'm sure, but I'll have someone wear a sling for four weeks. Now, if they're eating dinner or watching TV, I have them take the sling off. I seal the incision with the skin glue, so I let them shower the next day.

But when they're up and around, they should wear it. We've all had these crazy stories. You know, one patient I had had to sling off and bumped into a cantaloupe and tried to catch it with our operative arm, which is the dominant arm. And next thing you know, there, you know, it happens.

I think it's good to wear a sling when you're up and about is usually what I tell them. But usually after four weeks, you still have to use good judgment. Because it's probably not fully healed that tendon. From a life standpoint, though, you have to realize I'm not doing shoulder replacements on people that are having a little bit of pain.

They're usually pretty uncomfortable. They're pretty limited. So they've learned to live their life with the bad shoulder. So their life doesn't change much after the shoulder replacement. That's a great point. You know, they have their other arm, they can do things with, they don't have to walk on it. So that's not really been an issue.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So when do patients experience pain relief from the shoulder replacement? Let's say for arthritis.

Dr. Craig Cummins: You know, I always ask them that on a first visit and the arthritis pain is usually much better pretty quick, within a week, if not sooner. Yeah. Now granted at that point they're having some surgical pain, but definitely by the time I see them, two weeks later, they are probably having less pain than they were having before surgery.

Yeah. It's more of an ache, it's a surgical recovery type of pain, but that bad, gnawing, deep pain in their shoulder is gone. Right.

Dr. Eric Chehab: And then after a couple more weeks in the sling, that's when they can really start going on the recovery process to get the function back.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Yeah. And, I don't want to confuse people that, but there is a little difference between recovery rates of a reverse and anatomic.

So an anatomic replacement, they really need physical therapy.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So let's talk about the recovery for the anatomic shoulder replacement, the standard ball and socket. Okay.

Dr. Craig Cummins: So I'm much more conservative with their rehab and protecting that tendon we talked about earlier, because if it re-tears, they don't do that well.

And so you really have to get that tendon to heal down. And I describe that to patients and so we start therapy, but they're doing it in a safe manner to not overstress that repair. And I think that therapy is good too, because it's a constant reminder for the patients on what they can and what they can't do.

And so they recover slower than the reverse. In the end, I think it gives them a very natural feeling shoulder. Like I wouldn't say a 20-year-old shoulder, but a pretty normal shoulder after a shoulder replacement, but it takes time.

You know, we, I don't do any strengthening its range of motion early on, no strengthening really for months. I would say by four and a half months though they're doing pretty good. Like they're back playing golf or doing activities such as that, I mean not, not heavy lifting or weightlifting or, and it may be, you never want to get back to that.

But usually after six months, I've kind of removed any restrictions they can do what they want. But it is a mechanical part.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So you don't want to wear it down prematurely by doing a lot of heavy lifting for instance.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Oh, go ahead about the reverse. Yeah, the reverse is so different than any other shoulder recovery, because I rely very heavily on physical therapy for almost all shoulder operations post-operatively and for the reverse, I bet half my patients don't even go to therapy.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So they're getting moving right away. You don't have to protect that front door repair that you had done because it's probably not there. If they need a reverse.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Yeah. It's interesting because it's more of a fixed joint, they heal better for one. So when, if you do repair them, there's a high rate of healing and on, you know, when I've gone back the second time, it's almost always healed, or in some people it's a huge tear.

So that's a different issue and it's not even there, but they've done studies where even if it re-tears, it doesn't seem to matter much. People still do well. Right. So I mean, I do protect it. We do have sort of a protocol. Some people like to go to physical therapy and that's fine. It does change the mechanics of the shoulder.

So on one hand, people recover much quicker. But your body sort of has to get used to it. And if you do too much too quickly, sometimes people get some pain, you can get stress fractures are not common, but they can happen. So it's interesting. I'm usually having to slow them down. Cause they're coming back for the two-month visit and they're raising their arm up overhead and they're wanting to go back to doing everything.

And I'm like, I know you feel like you could, but just give it some time, you know?

Dr. Eric Chehab: And for many people it's been years since they've been able to raise arm up. Right? Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Some of the complications again, I think it'd be a good idea to divide it into anatomic versus reverse. Again, complications are rare, but they can happen.

What are some of the common complications a patient could encounter with a standard anatomic replacement?

Dr. Craig Cummins: I guess I can start with surgical complications which, in my experience, has been really uncommon.

I mean, almost zero, but when you pick a surgeon, you want to pick somebody that does a lot of something because you know, there's some big blood vessels nearby. I've never heard of anyone bleeding out from a shoulder surgery, but in fact, I can't remember the last time I've even transfused a patient for it, but that's, they're there and there's nerves in the area–very unusual to have a permanent nerve injury from shoulder replacement surgery.

But, you know, with the retractors particularly in like a big muscular guy, they could stretch a nerve that might, you might have a little area of numbness or something like that. That usually gets better. But temporarily in older patients, you could fracture bones as you're putting in these implants.

So you want to be a little bit careful. Now that we have the reverse, there's enough bailouts where at, I'm not sure it would overly affect the outcome, but it could lead to maybe a little longer operation and maybe a slightly different outcome than you were planning on.

So, those are probably the most common intra-operative in surgery complications. Afterwards, for the anatomic replacement, where you're matching their normal anatomy with the implant. I think my biggest worry is getting that tendon to heal. The subscapularis tendon. You gotta really protect it afterwards and surgically, you can do certain things to promote a better healing environment for it too because if that re-tears, granted, some of the people seem to do fine, but some of them do terribly.

And the next thing you know, six months later, you're putting in a reverse replacement. So it's another operation. Then there's infection, which is with any operation. But when you're doing joint replacements, it's more significant because those bacteria, they stick to the metal and they create a little coating.

So antibiotics can't get to them. And if you did get an infection, which I think the rate's pretty low, you know, one, 2% maybe it can lead to more surgery where you have to take the implants out and then wash everything out and come back and redo it. Shoulder is a little bit unique compared to some joints.

I think it's pretty rare. I don't even know if I've ever had one where you get like a, what you think of as a typical infection, where you get puss and redness and where you really need to operate on it. The shoulder, they tend to get infected with these low virulent organisms. They're not an obvious infection.

Usually people come back and they just have this low grade pain that doesn't go away. And it's very hard to even culture it. If you get a patient like that, I'll end up having to do a shoulder arthroscopy on them or I'll can get some tissue and culture that out. And you get these low grade infections, which you don't always necessarily have to re operate on, but that's a, that's a risk both with the reverse and the anatomics.

The reverse implants, early on, there was a fair amount of complications with it, because again, I think we were putting them in the worst-case patients, the ones that had had multiple surgeries or, and I think the implants weren't nearly as good as they are now, and the instruments to put them in weren't as good.

Because at first, it was a high rate of infection and that's all, that's all equalized with the other type of replacement. And then with 20 more years of experience with the–

Dr. Craig Cummins: –and we're better at putting them in. When you're doing a surgery, it's ‘how tight do you make the joint?’

And if you don't make it tight enough, then they can dislocate. Which I think used to, you know, across the country be more common than it is now. And I would say that's a problem that's fairly easily fixed if you have it. I mean, it might mean another operation. But you don't have to redo the whole thing.

You can just change a little bit of one of the implants and the problem is solved. And you know, you never want to operate on somebody twice. If you make it too tight on the other hand, it doesn't dislocate, but you can actually put too much stress on the bones that support the muscles around the shoulder, and you can get these like a stress fracture, like something a runner might get in their shin if they run too much.

So there is a little bit of an art how, how tight or not tight to put these implants in and, and a little bit, you have to judge it on, is this a 82 year old lady with osteoporosis? Or is this a 65-year-old male that used to lift weights? Those are the two things.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So the complications are pretty predictable that occur around advanced shoulder replacements and reverse shoulder replacements. We know how to treat those complications, but it's important that patients know about these coming into them. They're probably less than single digit percentage for some and no more than 5% for others.

I mean, it's rare these days with the modern prosthesis and the techniques to have a significant complication, but I guess every patient who has a complication, it's a hundred percent right. For them. But again, when you mentioned it's important to have an experienced surgeon doing these procedures to avoid these complications.

And then where do you see the future of shoulder replacement? Or do you think we've arrived?

Dr. Craig Cummins: No, they keep getting better. And some of it, I didn't even anticipate. I mean, the CTs we get now and the software to do the preoperative planning is great.

And these companies have come up with a, we used to have certain anatomic features that were difficult to deal with bone loss from the arthritis and they have augments that now support that. I mean, I have one patient now that had a replacement done somewhere else that it was not put in well, and I had to take it out and there's all this altered anatomy and bone loss.

So I took that implant out and then I got a CT scan and they are doing a 3D printing titanium individual shoulder for the lady and it's crazy. I've been to the, you know, where they do it actually, where you train now, they're doing it there now at the Hospital for Special Surgery, where they got a 3D printer and titanium and it, you know, the computer just goes down and builds this custom implant. So that's amazing. And we're learning how to get the implants to fixate to the bone stronger.

So where we used to put in these bigger implants, now they're becoming much smaller, which is nice. Particularly, if somebody, you know, they're older and they maybe lose their balance and trip and break their arm under the implant. Well, if you have a smaller implant in there, it's much easier to manage that situation.

So I think it's going to continue to evolve and then who knows what's going to happen with robot surgery and all that. It's not anything on the horizon right now for shoulder surgery, but yeah.

Dr. Eric Chehab: So, I want to thank you for being a guest on Illinois Bone and Joint’s podcast series.

We've been talking about shoulder replacement with Dr. Craig Cummins. So Dr. Cummins, thank you for joining us.

Dr. Craig Cummins: Thanks for having me.

Don't Miss an Episode

Subscribe to our monthly patient newsletter to get notification of new podcast episodes.